A 1001 Strings for a 1000 Rupee Dole! Entitlement or Belittlement of Women?

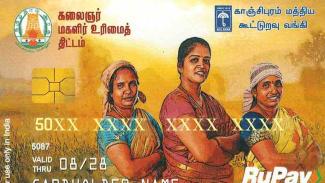

Recently, the DMK-led Tamil Nadu government and the Congress-led Karnataka government have implemented a monthly financial assistance scheme of Rs. 1000 and Rs. 2000 respectively for women fulfilling the poll promise.

TN Chief Minister Stalin has claimed it to be a historic step towards social justice in acknowledging the hitherto unrecognised work of women. He stressed that the scheme, under the Dravidian model regime of “everything for everyone”, was brought on the basis of lessons learnt from Periyar, Anna and Karunanidhi, and persistent with the state’s progressive legacy of women’s empowerment like the Equal Right in Properties (Amendment of Hindu Succession Act) for Women, 1989, etc. Implemented on the birth anniversary of Anna and the centenary of Karunanidhi, it is further affirmed as a revolutionary scheme that would lead to a new renaissance in the lives of crores of women.

Well, from the naming of the scheme - after DMK patriarch Karunanidhi, to its twin objectives of helping women to lead a life with self respect by eliminating poverty and improving their living standard, is there anything that is addressed at gender disparity? In a similar tone, Karnataka CM Siddaramaiah, after launching the “Gruhalakshmi” scheme that provides Rs 2000 assistance for women, has stated that if the fruits of economic development do not trickle down to the poor, cash transfers are an effective tool to raise their purchasing power.

The basic question is whether it is yet another scheme for elimination of poverty or is it for recognition of women’s work at home? The recognition of women’s work cannot be a mishmash of the two even as it could sometimes serve both. While Stalin has repeatedly voiced that it is not an assistance, but women’s right, scores of women have been left outside the purview of the scheme.

In fact, there are more exclusions than inclusions with several criteria for eligibility that leaves more than 50% of the state’s women population ineligible for the scheme. Only one married woman, above the age of 21, can be nominated from a family. Families with income above 2.5 lakh rupees per annum, domestic power consumption higher than 3,600 units, owning above 5 acres of wetland or 10 acres of dryland, central and state government employees, income tax payers, beneficiaries of social security schemes or welfare schemes like widow pension, old age pension, welfare board pension, etc. are all not entitled for the “entitlement” scheme.

Even out of the 1.63 crore applicants in the four phase enrolment, only 1.06 crore have been identified as eligible. Karnataka has enrolled 1.33 crore women from BPL and Antyodaya cardholders. If the purpose of introducing the scheme is to recognise the domestic work of women, why are a large section of women left out of its ambit? Are women above BPL, government employees or beneficiaries of other schemes not doing household work? Recognising some section of women and not recognising the other sections in itself is discriminative and devaluing women’s labour.

Is Monetising Domestic Work a Solution?

The discourse on recognition of women’s contribution to the society, particularly the domestic labour, has been gaining different hues in the last few years in the Indian scenario. In 2009, the National Housewives Union, the first of its kind in the country, was formed by women’s organisations in Kerala to fight for minimum wages and pension scheme. The union’s application for registration as trade union was however rejected on the grounds that the Trade Union Act doesn’t define household work as a trade or industry and that the government cannot be considered as employer in this case.

In 2012, Krishna Tirath, the then Union Minister for Women and Child Development, mooted a proposal that husbands part a portion of their salary to their housewives as honorarium. This was taken by a storm of opposition from BJP and men’s rights groups from conservative position that this violates family relationship. Women’s organisations criticised it for absolving the state’s responsibility, discounting the contribution of women to national economy and redistribution of family income as inconsequential to women’s lives.

There have been precedents of courts passing orders granting compensation in accidents in which the women succumbed by calculating their contribution at home in monetary terms. The basis of such quantification is not standardised.

In 2021, Kamal Hassan’s political party Makkal Needhi Maiyam in Tamil Nadu gave a poll promise to pay salary to housewives bringing back the debate. Following this, the DMK gave a poll promise of Rs 1000 assistance for women in recognition of the domestic labour. The Congress in Karnataka elections this year gave an assurance of Rs. 2000 allowance for women as part of its 5-point charter. In similar lines, Madhya Pradesh government has announced Ladli Behna Scheme with Rs 1000 assistance. The AAP in Punjab is yet to keep up its promise.

Obviously, whatever the tall claims, the financial assistance scheme for women have come as part and parcel of the populist measures of various governments. Even as it is a paltry sum, nowhere comparable or compensatory to the hard labour women put in, it is welcome as it at least provides a marginal relief from the strife of grinding poverty and inflation, but it cannot be a solution to the drudgery of household work or can break the patriarchal power dynamics in the family. Neither will it stop or reduce domestic violence and oppression or empower women to take decisions in family nor will it change the perception of women as burden/liability.

If income is the sole factor for the low social status of women, then large sections of working women should have benefited by now. The state needs to lay emphasis on increasing women’s education and employment opportunities and minimise the household work through creating subsidised services for cooking, housekeeping, laundry, child care and elderly care. This will break the gender stereotypes around household work and overturn the conventional role of women in the family.