Ambedkar and the Working Class Movement

14th April 2024

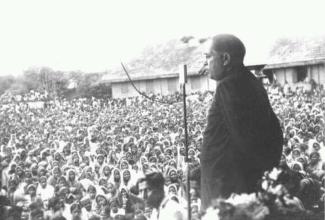

133rd Birth Anniversary of Babasaheb Ambedkar

Dr Ambedkar and

India’s Working Class Movement

- Ramayan Ram

14th April, 2024 will mark the 133rd birth anniversary of Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar. In today’s juncture, when dilution of workers’ rights are being justified in the name of ‘ease of doing business’, it would be more appropriate to look at the vision of Babasaheb on the rights of India’s workers.

There are three significant phases of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar's tryst with India’s labour movement. The first phase comprises the strikes in textile mills led by Girni Kamgar Mazdoor Union during 1928-29. This phase is marked by Ambedkar's initial engagement with the communist trade union movement and his recognition of the deep-entrenched caste biases inherent in the workers’ movement. During the second phase, in 1966, Ambedkar established the Independent Labour Party, a consequential move driven by his profound understanding of the intricate interplay between caste and class. While he comprehended the economic dimensions of class-caste exploitation, his focus remained steadfast on mitigating caste discrimination first to build up a class based unity of workers. The third phase of Ambedkar’s engagement with the labour movement was during his tenure as a representative of workers in the Viceroy’s Council of the interim government from 1942 to 1946. During his tenure, he showcased his instrumental role in shaping pro-labour legislation and policies for the Indian populace. Through these intersections, Ambedkar's commitment of advocating the rights and welfare of the labouring class resonates as a defining aspect of his multifaceted legacy.

Dr Ambedkar started his political journey as a working class leader with the formation of the Independent Labour Party in 1936. His decision to be in political life was inspired around contesting elections of provincial assemblies as per Government of India Act. Prior to this, he gained recognition as a Dalit leader, emerged from numerous struggles of Dalits, such as leading the fight to access water from Chavdar Lake, securing entry to Kalaram Temple, and advocating Dalit representation in round table conferences. Through ILP he was trying to build unity of workers on class identities. In an interview of 15th August 1936 to Times of India, he said that the fundamental aim of ILP is to advance the welfare of labouring classes. Ambedkar said, “Our organisation advocates the implementation of equitable goals and policies aimed at the emancipation of the labouring class, whose interests and relationships are prioritised by our party. The deliberate choice of the terminology, such as 'labourer,' over 'depressed classes,' underscores our recognition that individuals from marginalised communities, including Dalits, are encompassed within the broader labouring class.” In his party manifesto, he declared “Our party aims at safeguarding industrial workers, preventing unjust dismissals from their jobs, and ensuring fair promotion opportunities. We're committed to reducing work hours, ensuring fair wages, paid leave, and improving living conditions. Additionally, we seek to enact legislation for bonus, pension, and retirement benefits. We'll also push for social insurance to protect workers during illness or accidents. Our party will strive to build affordable and low-cost housing for the workers.”

In the Bombay Legislative Assembly, the ILP secured 15 seats which was much below Ambedkar’s expectations. He continued as an opposition leader to oppose the anti-labour policies of the Congress party. The main contention was the opposition to Industrial Dispute Bill 1938, which was tabled by the government to deny workers their right to protest. The bill stipulated that if the government declared a strike as illegal, the participants of the strike would have to face 6 months imprisonment. Ambedkar asserted that this legislation would turn workers to slaves, labelling it the “Workers Civil Liberties Suspension Act.” This law was even harsher than the Trade Dispute Bill of 1929. In September 1938, Ambedkar's Independent Labor Party and the Communist Party's AITUC led a massive strike against this law. Over one lakh workers joined the strike.

Earlier in January 1938 Ambedkar led a movement for the rights of rural agraricultural labourers. In the rural areas of Maharashtra the exploitative practices such as Khoti and Vantandari were prevalent for years. Khot were brokers, who acted as tax collectors from farmers on behalf of the British government. The Khot used inhumane measures to extort taxes. Similarly, the Vatandari system was widespread across various regions of Maharashtra. In this system, the government allocated land to Dalit labourers as a form of donation. However, in exchange, landless individuals were compelled to engage in bonded labour in the fields owned by landlords and tenants. In Maharashtra, the majority of Vatandars, or bonded labourers, were Mahar Dalits. In January 1938, Dr. Ambedkar initiated a movement in conjunction with the Congress Socialist Party to oppose Khoti and Watandari systems. This movement saw significant participation not only from the Mahars but also from a considerable number of farmers belonging to the Kunbi community. Twenty thousand farmers assembled and led a procession in Bombay. Dr. Ambedkar's efforts consistently emphasised an inclusive understanding of class and caste through the Independent Labor Party (ILP). However, during this era, the Communist Party refrained from openly supporting him, as the leftist leadership perceived Ambedkar's advocacy for caste issues as detrimental to the class solidarity of workers.

In reality, there was no organic solidarity between the labouring classes, along class lines, due to the caste discrimination inherent among Indian workers for years. Since 1928-29, Dr. Ambedkar has been asking the communist trade unions he has been working with to challenge the practice of untouchability and caste discrimination among workers and educate the non-Dalits about the discriminatory practices associated with the caste. He observed that the left leaders themselves were ambiguous on the caste question and were not able to convince workers about the problems of casteist practices. In 1928, amidst the fervour of the Bombay textile workers' strike, prominent left trade union leaders met Dr. B.R. Ambedkar urging for solidarity with the movement. While Ambedkar pledged his support for the strike, he articulated a crucial issue that the left unions should demand Dalit workers access to jobs in weaving departments of the mills. Notably, within textile mills, Dalit labourers were systematically excluded from this particular department which were deemed to be honourable, due to the requirement of mouth-held thread handling—a task deemed eligible only for upper castes and Maratha labourers. Dalit workers were assigned tasks of thread holding and cleaning. Ambedkar's insistence on eradicating this discrimination underscored a significant progress in the working class movement. Unfortunately, the communist unions and their leadership remained indifferent to this question. In 1928, a collaborative strike led by the left union, Girni Kamgar Sangh and Ambedkar's union endured for six months. Subsequently, the Bombay Government established a three-member committee to investigate and address the workers' grievances. Following the committee's report, Dr. Ambedkar penned an article in the newspaper Bahishkrit Bharat, wherein he said “The demand of untouchable classes to work as weavers in textile units is a matter of personal dignity. This demand was among the seventeen demands presented by the strike committee. Surprisingly, factory owners did not oppose it. However, objections arose from Maratha labourers, while the owners remained indifferent. In reality, owners were concerned solely with the completion of cloth production and the resultant profit, regardless of the caste of the workers. The issue lay in the objections raised by certain workers regarding untouchables working alongside them in the weaving section. What response could owners provide to such objections? Untouchables were permitted to work in other units, but were prohibited from the weaving department of textile units where wages were higher. The argument presented was that the presence of untouchables, such as Mahars and Chamars, in textile units would compromise the castes of Maratha labour, as weaving involved mouth contact.”

Dr Ambedkar observed caste biases as an obstruction to the class unity between the workers. On February 12, 1938, during his keynote address at the Dalit Labor Conference of Railways in Manmad, Nashik, Dr. Ambedkar delivered a seminal speech. It is in this address that he identified two main enemies of the Indian workers - Brahminism and capitalism. Emphasising his stance, he elaborated that Brahminism doesn't merely mean the privileges and power enjoyed by Brahmins, but the suppression of liberty, equality, and fraternity. And this thought is pervasive even beyond Brahmins. This demonstrated Dr. Ambedkar's insightful comprehension of both the potentials and limitations of the labour movement in India. To fortify the unbreakable unity of the working class, he advocated the eradication of casteism and also the caste system.

Dr. Ambedkar advocated reforms for rights of women workers. In 1929, the Maternity Benefits Act was enacted in the Bombay Provincial Assembly, a legislation co-drafted by Dr. Ambedkar and NM Joshi. Additionally, on August 7, 1942, Dr. Ambedkar proposed reducing working hours from 14 to 8 in the Viceroy's Executive Council. During the Seventh Labor Conference, Dr. Ambedkar emphasised the need for equal pay for equal work, paving the way for gender equality in workplaces. As a representative of workers in the council, Dr. Ambedkar visited the coal mines in Bihar and Maharashtra, gaining first hand insight into the lives of mine workers. He lifted the prohibition on women from working inside the mines. To extend maternity benefits among mine workers he proposed the 'Maternity Benefit Bill for Women' in the Central Assembly. This bill subsequently became a legislation providing eight weeks of maternity leave benefits for women. In independent India, these legal provisions were included in the comprehensive Maternity Benefits Act of 1961, ensuring the provision of all aforementioned benefits.

In 1946, Dr. Ambedkar resigned from the portfolio of labour member and presented a draft on "State and Minority" to the constitutional assembly. In this draft, he advocated nationalisation of agricultural land and supported state socialism. He argued that the labouring class should not be left at the mercy of private stakeholders, as private employers would never allow them to exercise their fundamental rights to unionise and strike. Many constitutionalists argued that the state should not intervene in the private, social, and economic affairs of the people, fearing it may infringe on personal freedom. Ambedkar countered it by observing that the state’s non-intervention in social and economic realm often translates to liberty for landlords and capitalists to raise costs and increase working hours, while simultaneously decreasing wages for workers. Therefore, granting unrestricted autonomy to agriculture and industry without state socialism would result in a monopoly of private stakeholders, jeopardising the fundamental rights of civilians.

Dr. Ambedkar regarded the welfare state's role to be essential for the success of democracy. That's why, amidst industrialization, he refused to compromise on the fundamental and democratic rights of workers and farmers. Private industries and market economies struggled against such rights. Therefore, the state socialism, with its checks and balances and controls on agriculture and industry, became crucial in safeguarding the rights and interests of workers. This is why Dr. Ambedkar supported a system of state socialism. He diligently strived to fulfill his duties and responsibilities towards the working class throughout his political life within the framework of bourgeoisie democracy.

Dr. BR Ambedkar’s struggles and vision played a historic role in shaping a modern India and in guaranteeing rights for the oppressed. As the chairperson of the Drafting Committee of India’s constitution he played a pivotal role in giving India a modern democratic constitution. Today, when India is being ruled by a regime that has unleashed a comprehensive and brutal attack on the secular and democratic fundamentals of the Indian Constitution and on the hard earned rights of Indian workers in order to serve the interests of crony capitalism, Ambedkar’s vision provides us the strength to fight back. Today, when the anti-worker Labour Codes adopted by the Modi led BJP government weakens workers’ right to unionise, strike, minimum wages and social security, Ambedkar’s historical role and vision for strengthening workers’ rights provides us the inspiration needed to intensify workers’ struggle against such an injustice and unjust laws.