Unpaid Labour of the Gig Economy: Free Advertising on the Backs of Workers

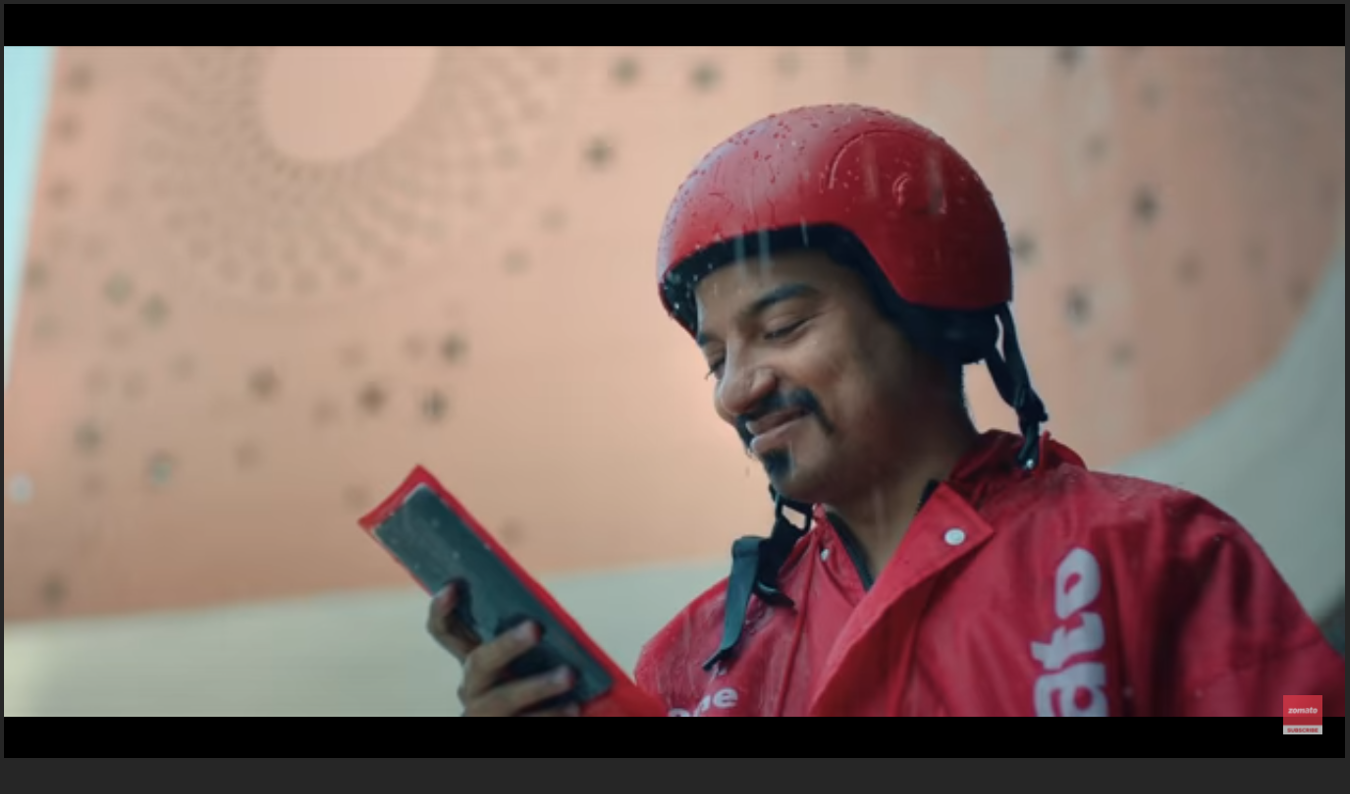

Zomato’s recent advertisement took the country by storm. It begins with a Zomato delivery worker in awe of having realized that he was delivering food to the Bollywood star Hritik Roshan, who says “Jadoo (magic), you reach on time no matter the weather, are you anything less than jadoo (magic)?”. The star proceeds to request the worker to wait for a selfie. While waiting, hopeful music engulfs the screen as the worker’s phone rings with his next delivery order. The worker promptly sacrifices the opportunity for a selfie with his hero and walks back into the rain for his next delivery. In the background, a voice of pride says, “Now if he stops here for a selfie, the next order would have gotten late. Whether it is Hritik Roshan or you, for us every customer is the star.”

Growth of the gig economy

Herein lies the true nature of the gig economy, in which the customer is king, no matter the cost. In a digital economy that is geared towards fast service and rewards minimization of time, companies compete to ensure that the customers are satisfied as quickly as possible. Food delivery platforms such as Zomato and Swiggy pride themselves in under-30-minute deliveries, in what is referred to as food “on demand”. The cruelty lies in the silence of the background. While customers sit back and wait for their order to be delivered, workers are rushing on their bikes to fulfil this unreasonable promise. As portrayed in the ad, workers are expected (without reward) to sacrifice themselves to ensure that the customer is the king, come rain or sunshine.

The gig economy has consumed India with the advent of tech-platforms driving consumption, such as Ola, Uber, Swiggy, Dunzo, Zomato, and Urban Company. Technology-enabled gig-work platforms are estimated to serve upto 24 million jobs in India in the next 3-4 years, soaring to 90 million in 8-10 years employing workers fulltime and part-time.

The problems with an economy being driven by such employment is uncertain work conditions and lack of protections. For example, Swiggy workers spend long hours, often extending to beyond 5 hours, waiting for an app to assign them orders, and only get paid for the orders they complete, not the waiting time.

Gig-workers denied rights under law

During the pandemic, several workers hit by the employment depression joined the employment of platforms like Swiggy and Zomato with the hope of eking out a living. App-based gig-workers face a plethora of issues. They are paid a base pay as a minimum delivery fee per order of Rs. 15 for 3 kms one-way, without payment for the return, which effectively results in workers earning as little as Rs. 15,000/- per month, despite providing skilled work, and having to work without any leave.

In February 2020, Swiggy’s valuation hit 3.3 billion dollars, the profits of which they invested in perfecting the algorithms running their apps. As these applications invest heavily in reducing human interaction and employment to algorithms, workers have a fixed set of minutes within which to deliver an order based on a route calculated by the algorithm. They are tracked by GPS, are to upload selfies showing their dressing, have to be in perfect health and must be extremely polite to sensitive customers as workers are at the mercy of their ratings. When a worker’s delivery is delayed, a “ticket” is raised regarding the late delivery, and after a few of such “tickets”, the worker’s ID is blocked. Workers are also prevented by the algorithm from logging out often, and their pay is cut if they choose “Black Zone/Safety Zone” as an option for rejecting an order. With customer, the king as their motto, this is the “service” upon which Swiggy and Zomato market themselves, and is the basis on which they make their profits.

The running costs of fuel and maintenance costs of the vehicle are all borne by the workers. Often, workers spent the major portion of their earnings in paying off EMIs for purchasing their vehicles. Workers have to find their own parking, and are often prohibited from parking in apartment buildings.

As Swiggy and Zomato continue to market themselves on the service and dedication of their workers, their sacrifice and immensely pressurized work conditions are glorified. During the COVID-19 pandemic, delivery workers worked at great personal risk without vaccinations or protections to ensure that the white-collared upper middle classes of the country were able to work from home but were subjected to casteism/classism by RWAs, discrimination, and abuse by the police.

For all their work, despite clearly falling within the definition of ‘workmen’ under the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947, they are deprived of benefits under the same and also denied social security including ESI, EPF, and gratuity. The companies use the subterfuge of terming workers as “delivery executives” and calling themselves “aggregators”, and use of terms as “partnership agreements” with the singular goal of denying them the rights available to workers, despite there being a clear employer-employee relationship. This is a stark affront to their right to equality, right to life and the right against forced labour recognized in Articles 14, 21, and 23 of the Constitution.

Free advertising

In its Red Herring Prospectus, Zomato wrote, “Our delivery partners, carrying and dressed in distinctive Zomato branded attire, enable us to offer a consistent experience to our customers, increase brand awareness and build positive brand affinity from which we believe that we could benefit with lower customer acquisition costs”. However, this gross misrepresentation fails to mention that workers pay for the uniforms and bags carrying the company’s branding.

Companies spend millions in curating and marketing their unique brands, creating awareness, employing measures to appear socially responsible, and working hard to leave an impression on the minds of consumers. In the financial year 2019 alone, Swiggy spent a whopping Rs. 778 crore on advertising and marketing. What these numbers do not reveal is that a significant portion of the marketing for these companies is performed by their own workers for free.

Not only do Zomato and Swiggy compel their workers to be in uniform at all times, they are also required to pay Rs. 1,500-1,800 for the food delivery bag with the brand logo, two t-shirts with the brand logo, and an extra Rs. 350 for the raincoat. Workers are forced to utilize the company boxes on their vehicles to carry their orders/food, and are also compelled to wear the uniform during the course of their employment. In essence, workers serve as a free platform on which companies such as Zomato, Swiggy, and Dunzo market their brands. As workers average more than 150 kms per day, they carry the branding of the companies across the city and provide free advertising for the company.

This is exploitation of workers in its most fundamental form. When a company advertises on billboards on roads, on televisions, social media such as Facebook/Instagram and newspapers, they spend lakhs for the space to carry their advertisement. A marketing campaign on Facebook alone which carries sponsored ads on the timelines of users cost the companies crores per year. No matter the platform, companies pay huge amounts for spreading awareness of their brand across to potential/existing consumers.

Not when it comes to their own workers. Workers are utilized as the free space on which the branding of these companies is carried across the country. Despite a direct link between the increased revenue from such advertisement (which is why the companies insist on uniforms being worn and branding on workers), workers are not given a fair share in the revenue made off their backs. When a person promotes a product or company, companies are contractually required to pay such persons for the promotion, including the lakhs that must have been paid to Hritik Roshan for the abovementioned ad. However, workers are not only denied a share in the profits made from their advertisements, but are also made to pay to carry the same.

Such free and forced advertisements not only violates the right against forced labour enshrined in Article 23, but is in gross violation of the right to life and dignity protected under Article 21 of the Constitution. Workers, being the owners of the t-shirts bought with their own money, are entitled to the revenues earned from the advertising space occupied on their t-shirts. Moreover, workers are entitled to a share in the revenues of the companies for whom they are providing free marketing space on their backs and vehicles.

What this portrays is a capitalistic contempt on the part of these companies towards their workers. Workers are being meagerly paid by these companies for their direct contribution of deliveries to the revenue of the companies, they are not paid for their marketing contributions.

As customers and companies track workers on screens, glorify their sufferings, and make profits off them, we must demand that workers be given a share in the profits generated by them. We should also demand that workers be paid a regular adequate monthly payment to the tune of a minimum of Rs 26,000 to lead a decent life irrespective of and in addition to orders, kilo meters, bonus and incentives. The pandemic has shown that the country comes to a screeching break and starvation if not for the blood, sweat and tears of workers keeping these companies running. We must agitate and organize to demand that workers be treated as equals with dignity. We must take back the profits made off our backs! π